these things don't hold water

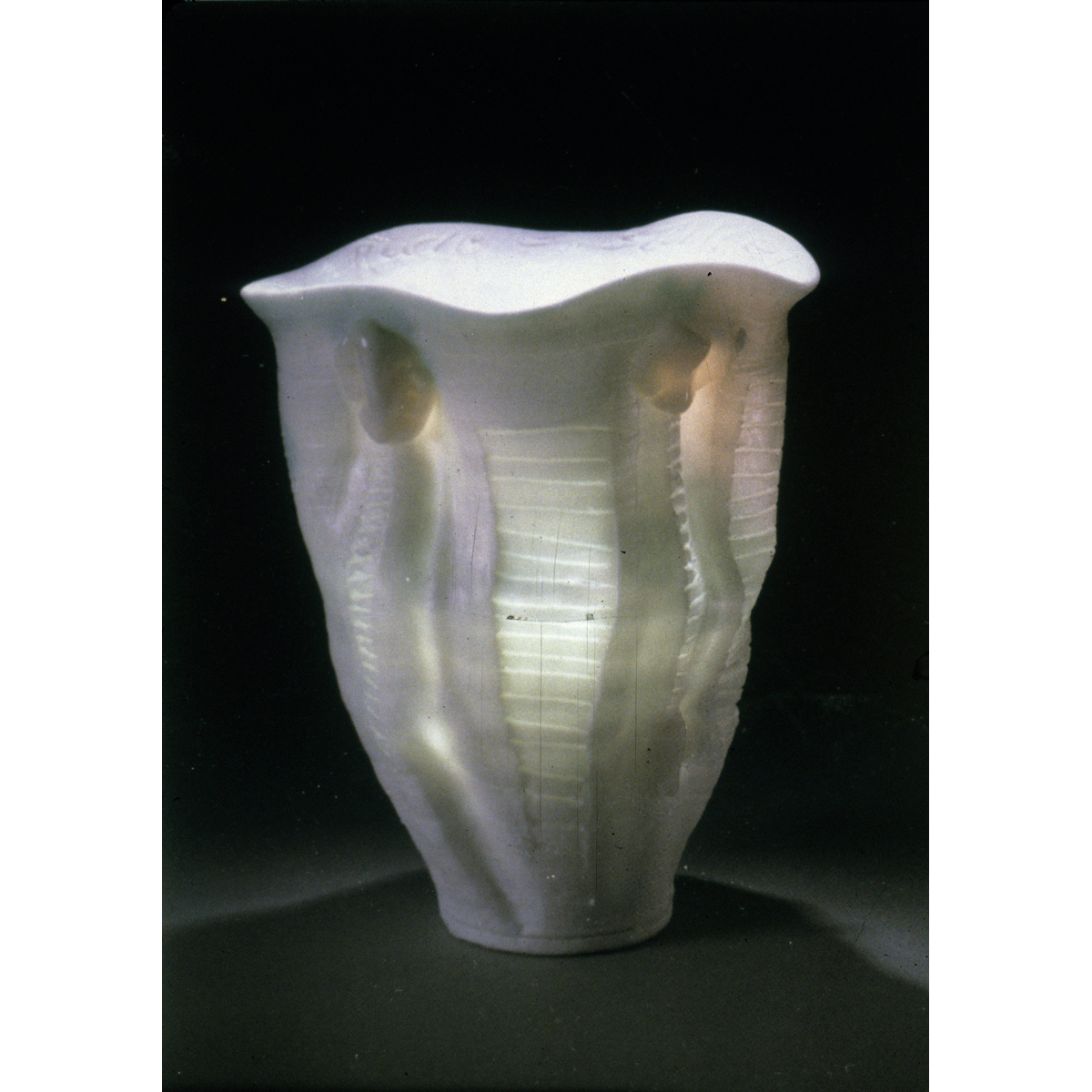

Rudolf Staffel, Light Gatherer, photo by the artist.

I wasn’t searching for it when I stumbled into one of Rudolf Staffel’s Light Gatherers at the Philadelphia Museum of Art years ago. It was just a random singular display, alit on a pedestal near the restroom I was headed to, my senses taking a break from searching for meaning in works of art. Words stopped when I came upon that piece, as if it had gathered my breath and thought along with the light. The idea of using the dense materiality of ceramic to hold the non-substantial opened a new landscape to me, focused as I had been on making pots for eating and drinking. The feeling of touch in the Light Gatherer lent a sense of imperfection; yet the form was radiant with light. The piece felt at once unrefined and transcendental. It was one of the first times I directly felt the metaphoric power of the vessel form, here showing the human wrestle with incarnation in the material world to reach for and hold the abstract, uncontainable mystery and power of light.

Rudolf Staffel, Bowl, 1969, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

We feel our way into a vessel’s metaphors of containment and purpose in a visceral way, making connections to our own lived experiences and emotional associations. The message from the utilitarian object is one of sensory allusion, within the context of the engagement posed by the function. For me, that Staffel piece evoked early memories of playing under a blazing canopy of leaves illuminated by sunlight; or sitting in church with my mom, gazing through the stained glass windows; or looking out from a warm house through a sparkling frosty windowpane at a snowed-in world. The idea that you could gather the source of those sensory impressions in a vessel caused me to envision human aspirations towards truth or goodness. It’s true that a vessel, with bounded interior and charged exterior spaces, serves as a metaphor for the body. But beyond that, there is symbolism of functionality: the vessel as a container can display or protect, preserve or serve its contents. Staffel’s pieces as gatherers operate with a gentle and open coalescence rather than an intellectual or intentional constriction. Thus the forms flow openly and loosely towards the light they gather.

Strainer and bowl.

These layers of metaphor are also embodied in work related to eating and drinking. Our relationships to food anchor us in the material world while also giving form to our intangible experience, using sensuous engagement to strike chords of meaning. Think of all the food metaphors we use in talking about our inner lives: we offer food for thought, or we talk about digesting information, having good taste, steeping ourselves in something, or putting something on the back burner. In the kitchen, we transform food into nourishment. The tools we use in that transformation – infusers, separators, grinders, reamers, sieves – can correlate to our emotional and mental processes. I am reminded of a passage from an Anais Nin novel in which she describes a character’s emotional state using a sieve as a metaphor: “Sabina had always moved so fast that all pain had passed swiftly as through a sieve leaving a sorrow like children’s sorrow, soon forgotten . . . [Now] The silvery holes of her sieve against sorrow granted her at birth had clogged” (From A Spy in the House of Love, p. 92-3). A sieve allows some things to pass while also determining what to hold onto, letting the liquids drain away to reveal the jewels. Keeping the flow moving is crucial.

sieve funnel, matte crystalline glazed porcelain.

Openwork in ceramics has always held my attention, whether it was cut away areas of a double-walled form that allowed peeks of the inner chamber, or forms that were more hole than substance that held a space at once apart and accessible. The latter constitute what I have come to call “breathable” forms – these allow for the passage of light, air, and water, while still providing a structured space to hold solid forms. In my work breathable forms range from sieves and separators to colanders and baskets, and include a series I tend to call bone bowls. What does it mean that these forms don’t hold water? The movement of air and water metaphorically keeps things fresh, keeps things from rotting or stagnating.

bone bowl, matte crystalline glazed porcelain.

This type of form breaks down the dichotomy of interior and exterior space; the inner life of the form flows seamlessly into the space around the form. It makes me think of the way Merleau-Ponty describes the relationship between the perceiving subject and her world. Instead of separating the organism from the environment, he connects them “through inherence of the one who sees in that which [s]he sees” (p. 163, The Primacy of Perception). It is in this undivided state that we live, caught up completely in the environment around us. The breathable form allows for movement back and forth; it, like the light gatherers, is not holding on so tightly to its contents, preferring a permeability in its boundary.

Staffel’s Light Gatherers opened me up to the symbolic level of functionality. Working on that level over the years, I sometimes produced an object with a less practical, more ambiguous function. My mom would say, “That’s a thinking thing.” She knew that that piece was developing ideas and that its function was to inspire musings, even though it looked like it may have some obscure use in the kitchen. A thinking thing may or may not hold water, but it does grow thoughts.

If you are in the Philadelphia area, there is currently a collection of Rudolf Staffel’s work on display in Gallery 119 of the Philadelphia Art Museum in an installation called At the Center: Masters of American Craft.